This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Executive Summary

Nuclear verdicts against corporations are on the rise.

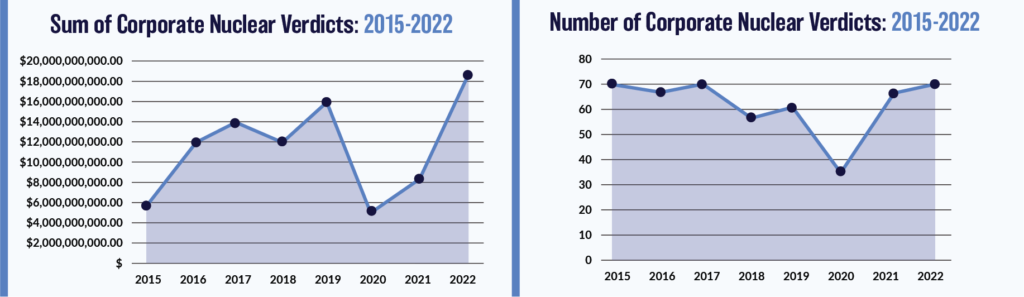

A new analysis by Marathon Strategies found that in the decade following the Great Recession, the median verdict greater than $10 million against corporate defendants grew 55%. The five years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic saw a particularly sharp rise in both the sum of these verdicts (178% increase) as well as their median (41% increase).

Though this trend was interrupted amid court closures in 2020, the sum of corporate nuclear verdicts nearly quadrupled in the following two years, from $4.9 billion in 2020 to over $18.3 billion in 2022. The median verdict also rose from $21.5 million in 2020 to $41.1 million in 2022 – a 95% increase – while the number of verdicts doubled. Civil court juries are once again issuing verdicts for damages in amounts that often rival the annual budgets of small countries, threaten to take down businesses, and provoke spikes in insurance premiums.

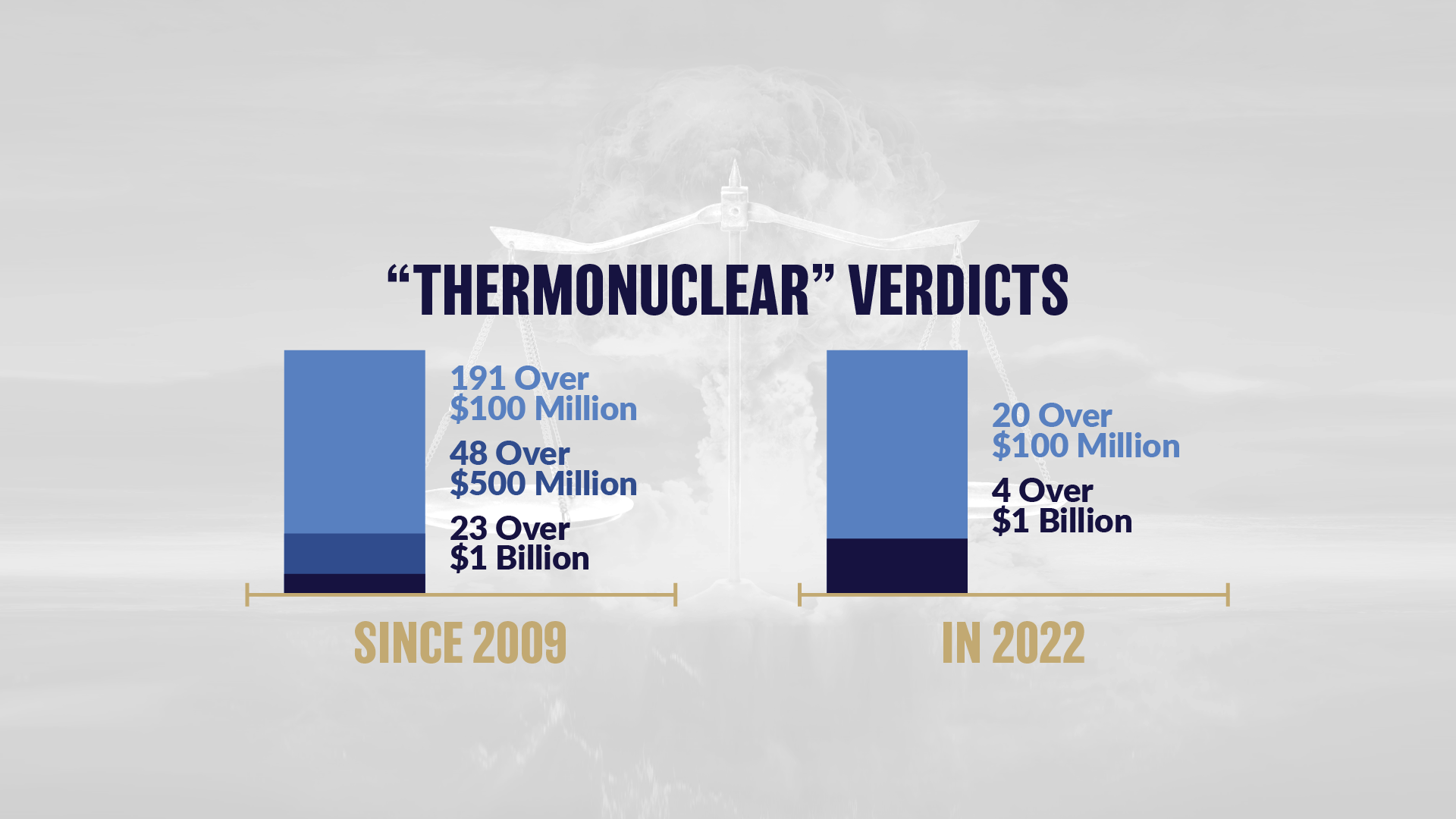

This report asserts that the term “nuclear verdict” no longer captures the scale of large jury awards.

Verdicts against corporations have become so large that those in excess of $100 million, at minimum, now necessitate a “thermonuclear” label. Juries ordered twenty verdicts against companies for over $100 million in 2022, including four that topped $1 billion. Overall, since 2009, 191 of these verdicts were “thermonuclear,” including 48 that exceeded $500 million and 23 that reached above $1 billion.

Marathon’s analysis identified 882 nuclear verdicts against corporate defendants for a total of $169 billion. As this report focuses on jury awards and not the ultimate outcome of each case, this total does not reflect reductions for comparative negligence or assignment of fault to settling defendants or nonparties; additurs, remittiturs or reversals; or attorney fees, costs, or other fines, unless awarded by the jury. In several recent cases – such as a 2022 intellectual property matter in which Meta was ordered to pay messaging app firm Voxer over $174 million in damages for violating two live-streaming patents – the defendant has either begun the appeal process or said they plan to do so.

Industry sectors enduring the biggest financial hits due to nuclear verdicts since the Great Recession include tobacco, pharmaceuticals, automobiles, finance, and IT software. Many of the verdicts made mainstream news headlines, including juror awards of $23.6 billion against tobacco and $9 billion against pharmaceutical giants in products liability matters. While the top industries for these verdicts may be self-evident – wrongful death cases from smoking have been litigated for decades, motor vehicle accidents are an entire practice area to themselves, finance is an industry with frequent contract disagreements, and technology is an industry fraught with patent disputes – few sectors have been immune to supersized verdicts. Marathon’s analysis found that since 2009, juries have ordered nuclear verdicts against some 712 companies across 117 sub-industries. Since the pandemic, the top sectors have included semiconductors, trucking, and big tech firms.

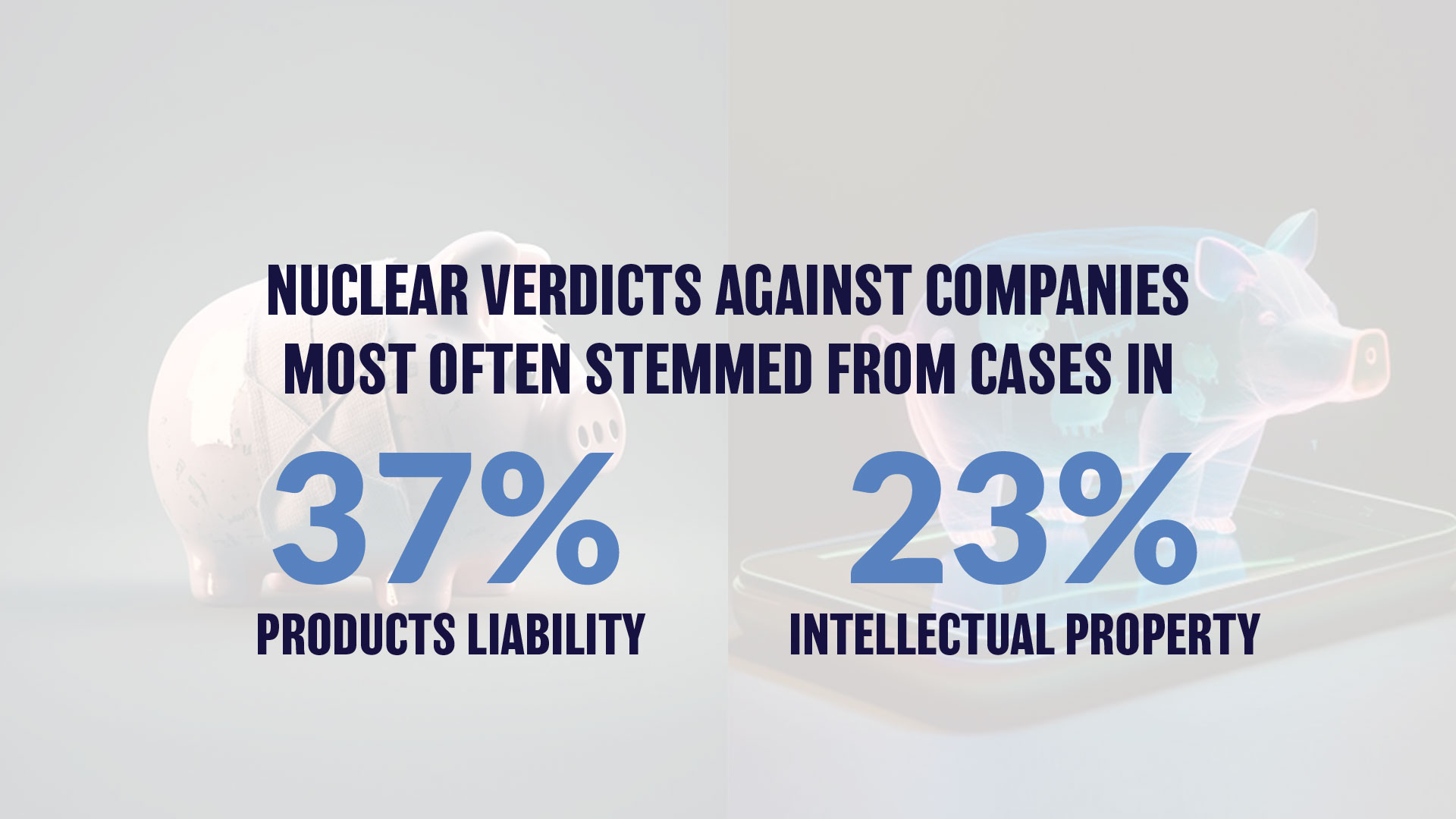

While each case is unique, Marathon’s analysis found that nuclear verdicts against companies most often stemmed from cases in products liability (37%) and intellectual property (23%) matters. Since 2009, there have been 211 products liability nuclear verdicts for $63 billion and 173 intellectual property verdicts for $41 billion. The next-largest case topics, breach of contract or breach of fiduciary duty, combined for 105 verdicts for $17.5 billion total. Other top cases for nuclear verdicts include motor vehicle (83 verdicts for $7.8 billion) or wrongful death accidents (6 verdicts for $8.2 billion), worker or workplace negligence matters (71 verdicts for $4.6 billion), and fraud (47 verdicts for $4.9 billion). As many cases contained allegations across several of these categories, Marathon’s data sorting prioritized the classifications determined by The National Law Journal and LexisNexis’ Jury Verdicts & Settlements database.

Nuclear verdicts span state and federal civil court districts across the country, but juries in some states have been more prone to handing them out than others. Since 2009, Texas, Florida, California, and Pennsylvania topped the list of states that have awarded the largest sums. Overall, state courts accounted for $108 billion in corporate nuclear verdicts compared to federal courts’ $61 billion. Interestingly, state verdicts dominated in Florida, California, Georgia, and Pennsylvania, while federal verdicts led in Louisiana and Delaware. While it is difficult to account for these discrepancies nationwide, generally, Marathon identified factors like local laws that encourage certain types of cases more prone to large verdicts, the presence or absence of limits on punitive damages, and court procedures that favor plaintiffs, among other factors.

This report on jury awards that surpass $10 million is a presentation of data as a recording of fact. It is intended to provide a comprehensive picture of both the large amounts awarded, as well as the speed in which they are occurring. The data is meant for both pro-plaintiff and pro-defendant audiences to analyze as desired. This report does not take an ideological position on these cases. It also does not draw case-by-case distinctions, such as differences between jury and bench trials or differences between the plaintiff as a company or as an individual.

This report attempts to focus on what common threads can reasonably be identified through such an analysis – namely, what industries have borne the brunt of these verdicts, which states and courts have been the sites of the largest sums, and which case types have been most frequently associated with them.

A myriad of reasons exist for the increase in the size of these verdicts. Industry analysts, public surveys, and media reports have identified corporate mistrust; social pessimism; erosion of tort reform; public desensitization to large numbers; and shifts in jury pool demographics, among others. To be sure, increasing nuclear verdicts are also linked to increasing corporate misconduct, such as CEO scandals and public controversies.

Some observers have also identified the proliferation of trial tactics such as “reptile theory,” in which plaintiff’s lawyers appeal to the “reptilian,” or emotional part of the brain, to trigger an instinctive safety response in jurors rather than the panelists relying on the rule of law in deciding cases and subsequent damages. Trial lawyers also use a tactic dubbed “anchoring,” in which they suggest an extraordinarily large award to a jury so that number becomes “anchored” in jurors’ minds. Others also employ the “joinder” practice to claims, linking lawsuits or several parties in one, to eschew venue requirements when shopping for a favorable litigation jurisdiction.

Policy makers in some states who believe these verdicts are out of control have attempted to curb them. After four verdicts against the Texas trucking industry in 2021, state legislators approved a bill aimed at hamstringing plaintiff’s counsel from using the reptile theory. The law, in part, bans lawyers from presenting evidence of a motor carrier’s failure to comply with an industry or company regulation or standard unless evidence shows that failure was a cause of the bodily injury or death for which damages are being sought.

The U.S. Congress has considered enacting legislation to require third parties investing in lawsuits in exchange for an interest in the proceeds of verdicts to disclose details about the funding. The controversial practice is currently unregulated and not fully understood. Advocates argue litigation financing enables plaintiffs who would not otherwise be able to afford a case with meritorious claims the necessary resources to bring one. Critics argue that the market has been rapidly expanding with virtually no regulatory oversight, and that the industry feeds nuclear verdicts because a funder can afford to hold out for a large settlement to maximize their return. From the corporate vantage point, this sort of investment, at times by private equity firms based on a portfolio of cases, can make it difficult to settle cases. Bloomberg estimates the financing of such cases at $39 billion globally in 2019 alone.

Other factors cannot be resolved through new or revised laws or policies. Each juror brings their life experience, biases, and sensitivities to the courtroom – with age, politics, pandemic experience, opinions about corporations, and more influencing whether they will side with the defendant or the plaintiff, and if they will issue a nuclear verdict.